|

What is Linux?

Linux is a 32 bit open source operating system. It is based on the very popular

Unix operating system and it’s code is

freely available (thus explaining the “open source” label as opposed to closed

source where the code is not available freely). Linux is often referred to as

being a “gathering of very cool software”. While this is not a bad description,

a more precise definition would reveal that Linux refers to a specific part of

the “gathering”. Linux points to it’s most basic element: the kernel. Everything

else that is bundled with the Linux you get is an application.

Figure 1.1 - Linus Torvalds is the founding father of Linux

Picture by Christopher Gardner

The

Linux kernel is the operating system itself. There are different versions and

they are released by a non-profit organization using a version number system.

Each time something is added to the kernel, a new beta or experimental version

is released. Generally, there can be up to 11 latest versions of the kernel

available.

The main ones being:

-

The latest beta

version:

containing all the new features. This version may contain bugs or unstable

code. Ex: 2.5.44

-

The latest stable

version:

this version is recognized as stable and its code is presumed without bug.

Ex: 2.4.19

-

The latest prepatched

versions:

these are Linux alpha version and are being tested before released. Ex: the

latest prepatched version for the beta version could be 2.5.8-pre3

-

The latest patched

version:

Finally, these are the patched versions for different major releases. They

contain corrections to different bug reports and are being tested.

The last

thing to know about kernel versions is the way the numbers are being assigned.

For a X.Y.ZZ version, X would represent a major release version. Y is a minor

release version and Z is a patch version number. In other words, when a bug is

found and a patch released, only the Z number will change. When a bunch of new

features are implemented and the need to do an upgrade is done, the Y number is

changed and finally, when a collection of upgrades have been done, when a major

improvement or code revision has been done, the X number will be revised. To

learn more about kernel versions, make sure to visit

www.kernel.org.

Here are some examples (at the time of this writing):

|

The latest stable Linux kernel tree is: |

2.4.19 |

|

The latest prepatch for the stable Linux kernel tree is: |

2.4.20-pre11 |

|

The latest beta version of the Linux kernel is: |

2.5.44 |

|

The latest prepatch for the beta Linux kernel tree is: |

2.5.8-pre3 |

|

The latest 2.2 version of the Linux kernel is: |

2.2.22 |

|

The latest prepatch for the 2.2 Linux kernel tree is: |

2.2.22-rc3 |

|

The latest -ac patch to the stable Linux kernels is: |

2.4.20-pre10-ac2 |

|

The latest -ac patch to the beta Linux kernels is: |

2.5.44-ac3 |

|

The latest -dj patch to the beta Linux kernels is: |

2.5.39-dj2 |

Distributions

As mentioned before, Linux is often distributed in different formats; there

exists many like it, each of them being bundled with loads of

software by different companies or

non-profit organizations. These formats are called distributions. They include a

kernel and a collection of applications, software, wizards and specific tools.

Figure 1.2 - The RedHat Linux distribution is amongst the most popular

distributions.

Packaging

Originally, open source software like Linux was provided as source code. While

this had interesting features, only hardcore developers could handle, compile

and play with the necessary files. Soon, binary files were available and usually

shipped with easy to follow instructions to compile them. Such instruction are

usually found in a Makefile which is generally a simple set of scripts and

instructions.

Even though source code is always available, binary files are now the most

current way to handle program installation in Linux. By using special

applications, it is possible to handle the installation of binaries without hard

user intervention. However, the format in which they are provided can differ

from one to another. Especially since some popular distributions have developed

their own proprietary systems to resolve packaging problems. For the exam, you

should know the major packaging solutions and some of their specific attributes.

Here are some examples:

-

Tarball: This is the

equivalent of a windows .zip file. Tarball refers to the TAR utility used to

build the packages.

-

RPM: (Red hat Package

Manager) This package manager was developed by Red Hat and is now being used

by a lot of other distributions. The RPMs carry information about the files

dependencies. This means that this system keeps information on what files

belong to which package. It simplifies the installation of programs because

whenever you need to install a file, it will tell you what other packages

should be installed.

-

DEB: (Debian Package

handling solution) This solution from Debian is much like the rpm’s except

it handles the file dependencies in a more efficient way, simplifying the

installation of patches and upgrades.

Licensing

Licensing in the Linux world is quite easy to understand. The software,

applications and even the kernel will fall under one of the following license

mode:

-

GPL: Gnu Public

License (www.gnu.org).

Basically, when a programmer decides to place his work under the GNU

license, he has an obligation to freely give his software, without charges

and to publish all the source code. Only shipping, handling and media can be

billed. Whenever the author makes updates to his software, he has to publish

it and publish the updated code to the public. Most of Linux falls in this

category.

-

BSD: Berkeley software

Distribution. BSD is basically the same as GPL except that it is less

restrictive as to the distribution and the and modifications.

-

Freeware: The author

of the software is under no obligation to release his code but will let his

software go for free.

-

Commercial software:

This kind of licensing is rare in the Linux community. Basically this is

when you need to buy the right to use a software, just like any Windows OS.

Linux

Command Prompt

The Linux command Prompt is called the Shell. Just as the DOS shell is

identified by a group of characters (C:\), the Linux shell is identified by its

own set of characters. Many different shells exist. The most commonly used is

probably Bash (Bourne Again Shell), but there are many others. Shells will vary

with distributions or users' taste.

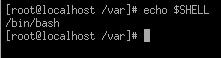

To find out what your shell is type the echo $SHELL command.

Figure 1.4 - Using the Shell to identify it

Daemons

A daemon is more or less the Linux equivalent of a windows service. It is an

automated process that manages resources, processes, etc.

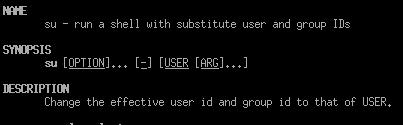

Man pages

The man command is a small command utility that outputs information about a

Linux command. This information is generally known as a "man page". To learn

more about the man command, simply type man man.

Case Sensitive

For many reasons including security reasons, Linux is a highly case sensitive

operating system. New users often encounter frustration when typing in commands

because they tend to forget this little detail!

2. Planning the

Implemenation

Linux Uses

Linux is a pretty flexible operating system. Although it has got a lot of

credibility over the years as a stable server platform, it is also an excellent

desktop platform. Databases, mail servers as well as many appliances can be

installed. Choosing the right hardware and applications is important as many

different solutions are often available to resolve a same issue. Using the more

conventional solutions is often advisable as updates and support will tend to be

available.

Hardware Compatibility

Linux supports most hardware on the market, with the increasing popularity of

the operating system, more manufacturers are bundling their hardware with Linux

drivers. Still, the vast majority of drivers available are coded by Linux users

so the more popular your hardware is, the more likely you are to find a driver

for it. It is a common idea that recently released hardware will tend to have

less Linux compatibility since most users will code their drivers on their spare

time.

File System and partitioning

Most distributions today have an option to automatically configure file system.

However, you should know how to configure the file system because server

platforms work better with customized file partitioning.

First, there are two major tools to configure system partitions: Disk Druid and

FDISK (this is the Linux FDISK not the DOS/Win version). Disk Druid is probably

the easier tool to use but FDISK offers performance and power.

Using these tools, you know have to partition the drives and assign the proper

file system to each partition.

System partitioning will follow different patterns depending on the system you

are implementing. It is common sense to plan this accurately in order to get

maximum performance. In a way, Linux partitioning is easier than windows because

it doesn’t rely on letters (A: C: etc). Instead, partitions have names. This

allows for better expandability. In theory, you could only have two partitions:

the root partition (represented by a “/”) and the Swap partition. Linux loves

Swap space and so it performs better on its own partition. Here is an

explanation of the different types of partitions:

-

/boot: Minimum 16m,

place for the kernels

-

Swap: Minimum 128m,

place for virtual memory. This should be increased up to the double of ram

you have. This is especially important if you are building a database server

as those are hungry for swap space. Graphic artist workstations will also

appreciate a nice wide Swap partition.

-

/ : (root) Minimum

250m, place for the basic core of Linux. It includes libraries, system

utilities, some programs and the configuration files.

-

/Var : Minimum 250m,

place for the files that change a lot (logs, mail server components and

print server spool files are examples). This should be increased if you are

using a server that handles a lot of entries. Mail servers or computers with

a lot of security auditing are examples here.

-

/usr : Minimum 500m

(should be more than 500m), more or less the equivalent of Program Files,

programs and applications come here. An application server should have a lot

of space here.

-

/home : Minimum 500m

(should be more than 500m), again, more or less the equivalent of “My

Documents” this is the place where the users have their files and specific

configurations. File servers should be putting a lot of space here since

most users tend to fill up their home folders.

These

partitions should be using one of the following file systems:

-

Ext2: this is the most

common file system for Linux. It offers stability, file permission and speed

although it is very sensible to power failures or improper shutdowns. The

reason is that it caches data before writing it to disk. In the event of a

blackout, the data in the cache might get corrupted. This forces the system

to run FSCK on the next boot to detect corruption.

-

Linux Swap: As its

name says, this is the preferred file system for the swap partition.

-

ReiserFS: This is a

“newer” Linux file system. It is a journaling file system which basically

means that every new entry to the drive gets a corresponding entry in a log

(journal) file. In the event of a power failure, the file system can rebuild

the missing entries instead of going into extensive integrity checking.

-

Ext3: This is supposed

to be the next Linux Journaling file system. It is currently still under

development and may never be adopted since ReiserFS is growing in

popularity.

Popular

Applications and Services

The following are key applications and services used in the Linux world. You

should understand what they are used for.

-

Apache: This is the

number one web server for Linux.

-

BIND: (Berkeley

Internet Name Domain) is the most used DNS server on the internet. It is

built on a strong architecture, it is secure and reliable. (http://www.isc.org/products/BIND/)

-

Ipchains: This is used

as a firewall, router, gateway, etc. It supports IP masquerading, port

filtering and transparent proxy.

-

KDE: This is a

graphical user interface based on the Xwindows system like Gnome (www.kde.org).

-

Postfix: A Sendmail

alternative with many other options (see also Qmail) (www.postfix.com)

-

Qmail: A Sendmail

alternative with many other options (see also postfix) (http://www.qmail.org)

-

SAMBA: SAMBA is a SMB

client/server application (just as any windows server) that provides smb

file and print services. In other words it enables a Linux server to become

a file server for a Microsoft based network. (www.samba.org)

-

Sendmail: This is a

mail transfer agent. Despite what it is called, it doesn’t just send mail.

It is a very complete mail tool that can handle most mail server operations.

(http://www.sendmail.org)

-

Squid: This is used as

a proxy server. Its main function is to cache frequently accessed and to

control access to web content. (http://www.squid-cache.org)

-

Xwindows or Xfree86:

This is a graphical user interface just like Gnome and KDE (www.Xfree86.org)

Software

Availability

As you might have seen from the previous sections, most software for Linux is

freely available on the internet. Most distributions will be also available in

stores near you and will usually carry more goodies than the downloadable

versions (often including tech support).

Advantages of Choosing Linux

One of the most noticeable features of Linux is it’s free nature. With the high

cost of licenses associated with commercial operating systems, a small priced OS

is often more than welcomed by many management staff. However, the most

important feature of Linux is its open nature. The fact that the code is

available to everybody makes sure that any bug can be resolved by anyone with

the proper skills. Note that Linux has also a reputation for having excellent

performance and reliability.

3. Installation

Media

Linux installation can be done using a variety of different media. Each

installation method has different pros and cons depending on the environment you

have. Here are some examples:

-

Boot disk: The boot

disk or boot floppy is generally not an installation technique by itself.

You will use a Linux boot disk in order to launch setup using one of the

other media types. These disks are usually provided as floppy images on the

cd-rom itself along with the proper software to copy them on floppies.

-

CD-Rom: This is the

most common type of installation. To do this, you need to have a system that

allows for cd-rom booting. You also need a Linux distribution on cd. To

start setup, you simply need to insert the cd-rom and start the computer.

The setup should start automatically. If your system does not allow for

Cd-rom start up, you can launch the system using a Linux boot setup disk.

-

Other methods

including Http, FTP, NFS and SMB are generally used as an enterprise

solution to deploy servers or workstations. All of these methods are network

based and are not necessarily common.

Installation modes

Originally, Linux installation was a painful process which could only be done by

a small elite group of users. Now, some distributions are even easier to install

than other commercial operating systems.

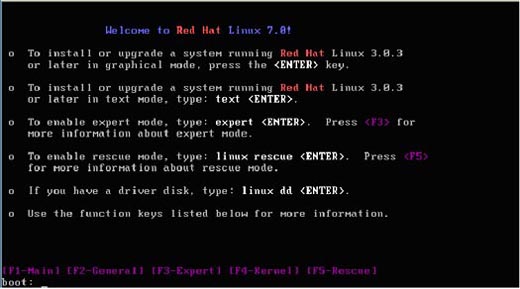

Once you have launched setup using one media or another, you will be faced with

the option to use either a “simple” mode or an “advanced - expert” mode. What

this really refers to whether you are going to use a “graphical user interface”

mode or a “text” mode. The GUI mode is a more straight forward process, it is a

wizard like experience featuring point and click menus. On the other side, the

text mode will often give you the opportunity to make a more personalized

installation. The downside of a text installation is its harsh nature.

Figure 3.1 - Installing Linux in text mode

Whichever mode you are going to use, keep in mind that the best instructions are

always the ones that come with your specific distribution. Common elements to

every distribution generally include:

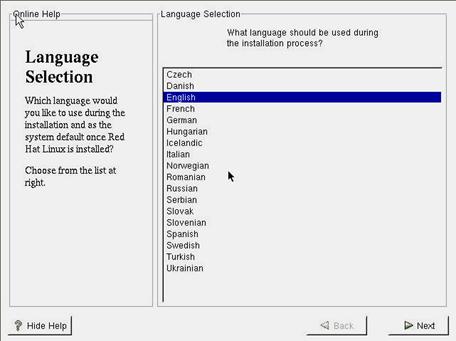

Setting up the language

Figure 3.2 - Choosing your language

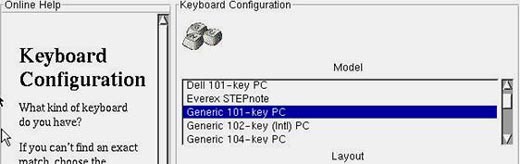

Setting up the Keyboard and mouse

Figure 3.3 - Configuring the keyboard

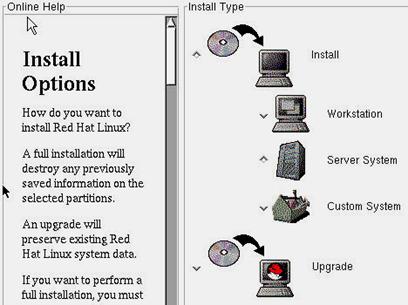

You

will then get to choose which kind of system you want to build. Depending on

your choices, the rest of setup will differ. A workstation setup is generally

straightforward and automatic. On some distributions, a workstation installation

will generate automatic partitioning and will be easier than a server or custom

installation.

Figure 3.4 - Choosing what kind of installation should be done

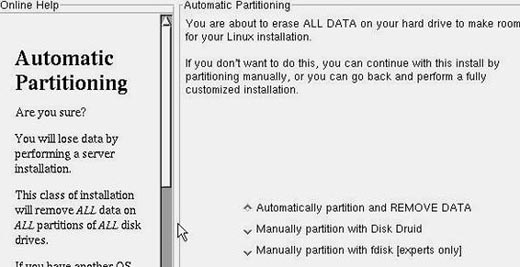

Then, you will get the chance to choose what partitioning scheme you are to use.

Automatic partition is the easiest way to go but not the preferred way of doing

it. If you remember section 2 (planning the implementation), you might want to

customize your partitions for your specific needs.

Figure 3.5 - Choosing the partitioning method

You

need a good practical understanding of the Fdisk command in order to pass the

Linux+ exam. I suggest you practice this a lot.

Figure 3.6 - Using Fdisk to make partitions

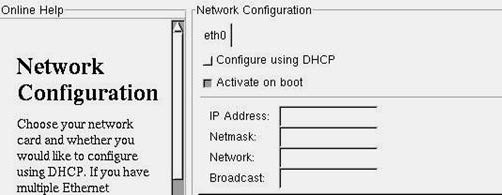

The

next step is to configure network settings. The ethx on the top is the Ethernet

adapter. If your network has a DHCP server, you may want to let the setup to be

automatically configured.

Figure 3.7 - Configuring Network settings in GUI mode

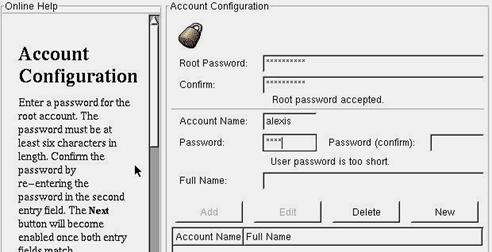

During setup, you will be prompted to give the root account a password. I

suggest you give a strong password as this is the most important account on the

system, the one with all the privileges. It is also recommended to create at

least one user account.

Figure 3.8 - Creating a user account

If

you went through the server or custom setup, you will need to configure the

packages you want in order to personalize your installation.

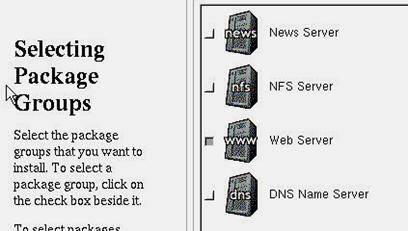

Figure 3.9 - Configuring the packages for a Web Server

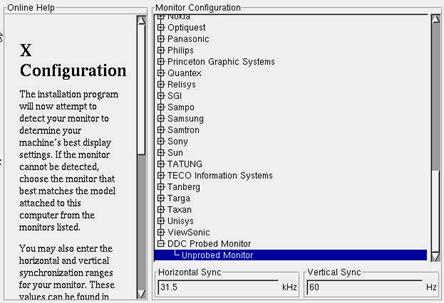

Depending on your installation, you may have to configure the Xfree86 engine. To

do this you will have to choose a monitor and configure its vertical and

horizontal refresh rate. Choosing a brand name screen will generally ease this

step as most manufacturers will be listed.

Figure 3.10 - Configuring a custom monitor with its respected refresh rates

If

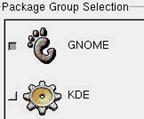

you chose to install your machine as a workstation, you will most likely need to

choose a desktop environment such as KDE or GNOME.

Figure 3.11 - Choosing your desktop environment

Graphical Interface Startup

In a lot of distributions nowadays, you might be asked during setup to directly

boot into the graphical interface. It is strongly recommended not to do so for

security and stability reasons.

Post-Installation tasks

Once the interactive portion of setup is done, the packages will be installed

and the kernel will be compiled. Speaking of kernel compilation, it is important

that you understand that the Linux Kernel can be compiled at any point after the

installation and the reasons for that.

Although the kernel shipped with your distribution is probably very good and

stable, you have to understand that it is built to work with most hardware and

systems available on the market thus making it full of code that you will

probably never use. Therefore recompiling your kernel will enable you to

optimize it by picking only what needs to be in it. Other reasons to recompile a

kernel will generally include: upgrading your system, doing hardware changes,

adding or removing features, etc.

After setup is done, you might also want to take a look at the installation logs

to make sure everything went fine. Most distributions will have the following

logs:

|

Location |

Description |

|

/var/log |

Location of most application logs |

|

/proc/ |

Hardware information |

|

/etc/rc.d/ |

Most system initialization, startup and shutdown logs |

|

/etc/syslog.conf |

This file contains the name and location of your system log files |

Installing more applications

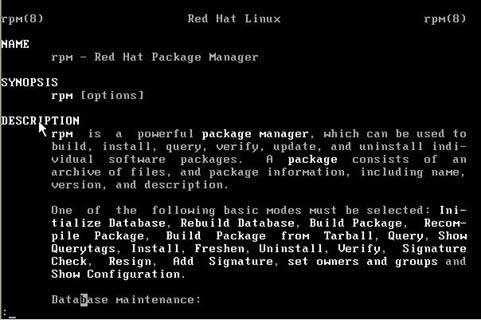

The way that you install additional applications depends on their format. A .gz

application format can be installed using the gunzip .gz command. A .tar

application can be installed using the tar –xvf .tar..tar command. These two

commands will uncompress the files required for installation. You are likely to

go through compilation before the applications work. An .rpm file can be

installed using the rpm command. For more information on installing and

compiling software, check out

Installing Linux Software.

Figure 3.12 - Man rpm output

The

rpm command has a wide variety of parameters and options. Make sure you know how

they work before taking the test!

4. Configuration

Now

that your Linux installation is done and verified, let’s take a look at further

customization.

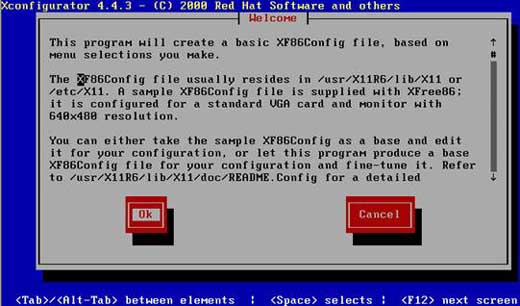

Configuring your Xwindows

No matter what desktop environment you chose, it is most likely that it will use

the Xwindows architecture. This is why you should know how to reconfigure your

Xwindows using automated utilities such as Xconfigurator and XF86Setup.

Figure 4.1 - Xconfigurator under RedHat

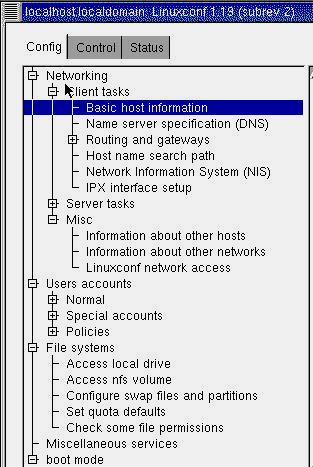

Configuring Networking

Networking, remote access and network clients can be configured using the

Linuxconf utility. (Simply enter linuxconf at the command shell). Specific

distributions have optional commands available like RedHat’s Netconfig.

Figure 4.2 - Using Linuxconf in GUI mode

Using Linuxconf, you can do most basic configurations, not only networking,

including network server related tasks. For example, you can use Linuxconf to do

basic NFS configurations like in figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 - Configuring NFS with Linuxconf

Depending on your distribution and the version of Linuxconf you have, you should

be aware that limited configuration of the following can be accomplished: X,

Samba, NIS, NFS, Apache, SMTP, POP, SNMP, FTP, etc. This includes access rights

for each of those services.

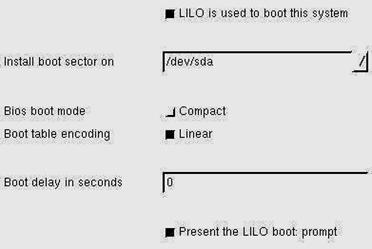

Configuring the Boot Sector

Linuxconf will also let you modify the way your system boots by changing LILO

(the Linux loader)

Figure 4.4 - Changing Lilo with Linuxconf

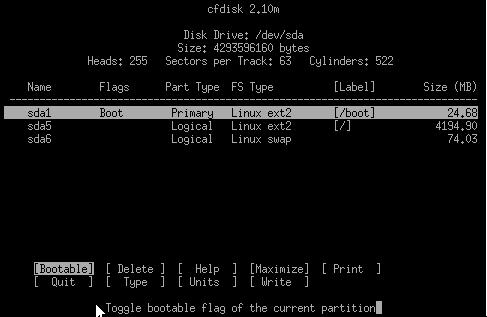

Configuring Swap Space

In order to work properly, your Linux machine needs some hard disk space to work

with. When your system gets heavily loaded, it may become necessary to increase

this space. When you add memory, you will need to increase your swap space too.

The recommended size of your swap space is the double of the amount of ram

memory you have. In order to keep things clean, Linux dedicates a partition for

this disk space. It is called the Swap partition. To view your Swap partition,

use the cfdisk command.

Figure 4.5 - Viewing Swap space with cfdisk

You

can then use cfdisk to delete and create a bigger swap partition. Once this is

done, activate it using mkswap.

Configuring printers

Configuring printers used to be a real problem in Linux as the printing industry

had no real standard before Postscript came. Today, simple tools exist. Specific

tools exist for specific distributions but in many cases, the printtool utility

tends to be a winner. You can also use Linuxconf to configure some printers.

To configure a printer, simply launch the printtool command in your desktop

environment (from a shell).

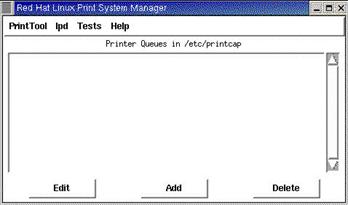

Figure 4.6 - Looking at printer queues with printtool

Installing other Hardware

When it comes to hardware installation, you should always make sure to follow

the manufacturer’s instructions. While Linux is becoming an easier system to

configure, you will generally have to refer to specific recommendations in order

to make sure not too damage your new hardware. The boot process contains a phase

where it will try to auto-detect new hardware and Linuxconf can help you

configure new monitors and others.

Editing Configuration Files

Linux is mainly configured using simple text files. Interfaces like Linuxconf

simplify this kind of configuration but also limits the possibilities. This is

why you are expected to identify and edit the configuration files. Here are the

files and their paths:

|

Configuration file |

Path |

|

Red Hat’s config directory |

/etc/sysconfig |

|

System initialization file |

/etc/rc.d/rc.sysinit |

|

Suse linux config file |

/etc/rc.config |

|

Config file for custom commands |

/etc/rc.d/rc.local |

|

Kernel module initialization file |

/etc/rc.d/rc.modules |

To edit a text file, simply use VI. You should have a good understanding of the

/etc/initab file before taking the exam. This file enables you to set most

environment variables. These are default values for specific parameters in your

Linux system (default language, type of shell you are using, etc). It is a very

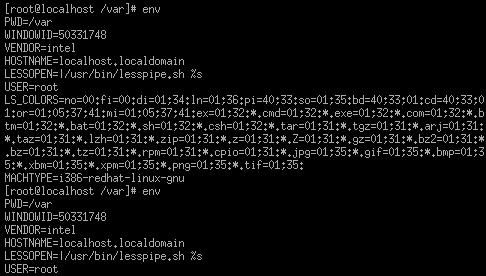

important file! To see your environment variables, you can enter the env

command.

Figure 4.7 - Listing the environment variables with env

Playing with Modules

Modules are a part of the operating system that resemble a cross between device

drivers and small kernels (sort of). Large parts of the kernel itself could be

divided into modules. This would enable you to have a lighter kernel. However,

having too many modules would also bring performance problems. Modules take

charge of specific functions, generally peripherals (the USB module, for

example, has long been separate from the kernel for stability reasons). To list

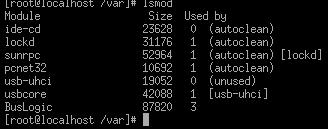

the currently used modules, you use the lsmod command.

Figure 4.8 - Listing installed modules with lsmod

To

install a module, you can use either the insmod or modprobe

command. To unload a module from the kernel, you will use the rmmod

command.

5. Administration

As

with any other operating system, administration efforts are necessary for any

linux system. These include the following tasks:

User Management

Linux is a multi user environment which means it is optimized to receive

multiple user sessions at the same time (many people can connect and interact

with the system at the same time). Therefore, carefully adding, deleting, and

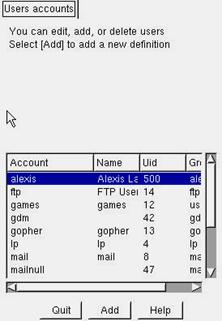

modifying users is necessary. You can add and delete users using Linuxconf.

Figure 5.1 - Adding and deleting users with Linuxconf

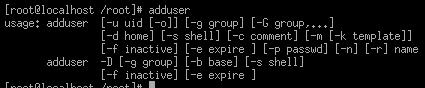

Adding users can also be done using the adduser shell command.

Figure 5.2 - User management using the shell

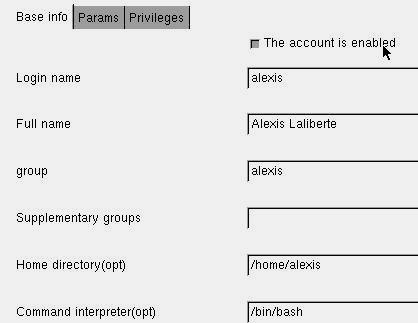

Linuxconf will also let you modify each of your user accounts.

Figure 5.3 - User management using the GUI

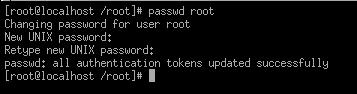

If

you want to modify a user's password using the shell, simply type passwd

<accountname>.

Figure 5.4 - User management using the shell

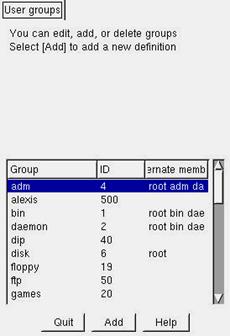

Group management is also possible using Linuxconf

Figure 5.5 - Group management using the GUI

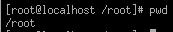

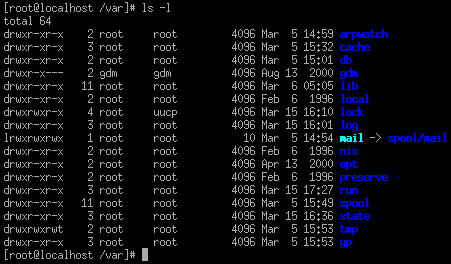

Surfing the File System

Before giving out permissions to files, you need to be able to navigate through

the file system. The first command you might want to use is the pwd command.

This will tell you the folder in which you are currently working in.

Figure 5.6

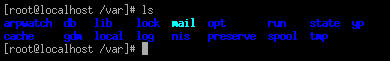

To

list a folder's contents type the ls command. Typing ls -l will

display additional attributes about each file and directory including

permissions, file type, size, owner, date and date last modified. For more

information on the LS command, type man ls.

Figure 5.7

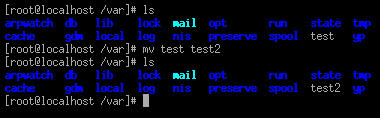

The

mv command renames and moves files.

Figure 5.8

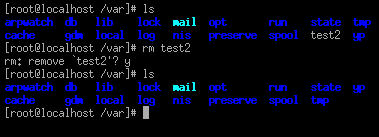

The

rm command removes files

Figure 5.9

To

move from a directory to another use the cd command. This command, like many

others in Linux, is not far from the ones found in MS-DOS. However it is a bit

pickier on syntax. To jump back to the root of the file system, type the cd /

command. To move up a directory, type cd .. (make sure to put a space

between cd and ..). To move to a specific directory, type cd

<path/directoryname>.

Using the Super User command

Before you can change file permissions, you need to understand that Linux is a

very secure environment. It is recommended to avoid logging in as the root user.

Using a regular account you can do most administrative tasks. Whenever

privileged use is necessary, simply type the su command. You will then be

prompted for the root password and voila! The moment you are done with your

tasks, type the exit command to stop being a super user.

Figure 5.10 - Man su output

Managing File Permissions

Because Linux is a multi-user environment (it allows multiple user to connect to

one machine in order to access resources), it is important to secure its

resources. To view the different permissions associated to files, type the ls

–l command.

Figure 5.11

It

is absolutely vital that you understand how the permissions work. The

permissions are identified by the first column of characters. Every letter has a

specific meaning. The rights column can be interpreted the following way:

|

Object type |

Group rights |

Owner of file rights |

Others' rights |

|

Character 1 |

Characters 2-4 |

Characters 5-7 |

Characters 8-10 |

|

d = directory

l = link

- = file |

r = read

w = write

x = execute |

r = read

w = write

x = execute |

r = read

w = write

x = execute |

A missing permission is represented by a dash (-).

Permissions are given values.

-

Read = 4

-

Write = 2

-

Execute = 1

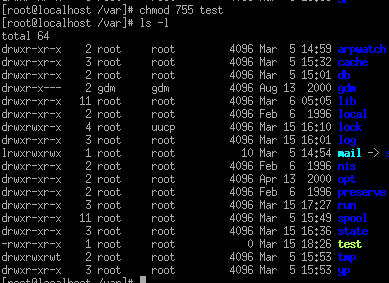

The

command used to give those values is chmod. To give read write and execute to an

owner, read and execute to groups and others for a specific file you would type

chmod 755 <filename>. If you need further help with permissions, check

out this

CHMOD Calculator.

Figure 5.12 - Changing test file’s permission with chmod

You

can also use chown to change the owner of a file and chgrp to

change a file’s group.

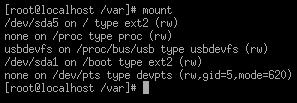

Accessing file systems and related devices

In order to use a disk device, it needs to be active or “mounted”. The mount

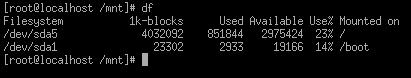

or df command will enable you to see which disks are mounted.

Figure 5.13 - The Mount command gives you the mount points and device status

Figure 5.14 The df command gives you physical disk information

This indicates which disks are currently active. The mount command activates on

startup. You can access most devices starting with the root. Removable devices

will be placed under the /mnt folder. However, if you want to mount a different

cd drive without rebooting the system, you will need to mount it.

To unmount a device, use the umount command.

Managing Remote Systems

Linux is a great system when it comes to doing remote administration. You can

connect to a remote system using many different techniques. Here are the most

common ones:

-

Telnet: This command

will enable you to connect to another computer and establish a shell

session. You will then be able to enter commands just as if you were

directly in front of the remote computer.

-

Ssh: ssh is more or

less the same thing as telnet except it is a more secure way of doing it.

Telnet uses clear text authentication and no encryption. Ssh is using a more

secure authentication mechanism that can even use security public

certificates and it then encrypts the whole session.

-

Ftp: The ftp command

enables you to connect to a ftp server enabled machine and manage files.

This is a very common technique on the internet and most people don’t really

know about its potential. Ftp stands for File Transfer Protocol and can move

files from one computer to another. It contains many commands that you

should have basic knowledge of.

-

You can also redirect

an Xwindows session or use a remote desktop software like AT&T’s VNC.

Runlevels

and init

Think of runlevels as different modes in which linux can operate (just as

windows can start in safe mode or regular mode). A runlevel is defined when the

computer starts up. When it boots, Linux starts the kernel which loads a first

process called init. This process monitors the system run state and then

consults the init table (located at /etc/inittab) to start daemons and the other

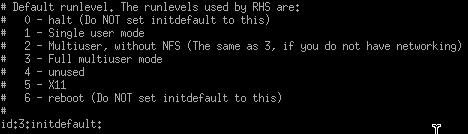

processes. The init table file contains information on the runlevel. There are 7

levels:

Figure 5.15

And

as you can see, the default is set to 3. Setting the level to halt or reboot

will force the computer to shutdown or reboot upon startup (which is not a very

good idea unless you want to make a bad prank).

Text Editors

To edit the different Linux configuration files, a simple text editor will do

the job. Linux includes many of these. You should know the most popular of them

and their basic functions. VI and EMACS are amongst the most widely used of

these tools. To start either of them simply type vi or emacs at

the shell.

Using the VI text editor

A very important aspect of the Linux file system is to create, edit and save

system configuration files. One way to do this is to use the VI text editor. To

edit a file, type vi <filename>. To create a file, type vi

<new_filename>.

Figure 5.15 - Either VI or VIM will be invoked by the VI command. Both are good

text editors

To

learn more about VI, I recommend reading the man vi output or reading

Using the VI Text Editor

Using the Graphical User Interface

To start the graphical user interface from the shell, type the startx

command. Navigating through the GUI is much like Windows nowadays. You will

encounter specific functions depending on the distribution and desktop

environment you’ve chosen.

Figure 5.16 - A nicely customized KDE desktop in action. Picture courtesy of

Sean Parsons.

I

recommend you practice using the KDE and Gnome environments before taking the

test.

Basic Shell Scripting

The most powerful feature of Linux is its scripting possibilities. It is assumed

that you have reasonable knowledge of common script commands in order to pass

the Linux+ exam. Here are the main scripting commands that you can use:

-

Find : As its name

implies, the find command is used to locate different files, folders, etc.

-

grep: This command is

useful to search for text contained within files. The output can be put into

files, etc. This can be very useful to automate log scavenging and

inspection.

-

cut: This is used to

be more specific within your searches, to filter the elements you are

looking for, etc.

-

if: The if command is

also used to screen out information by providing conditions.

6. System Maintenance

In

order to keep your Linux system running smoothly, it is vital to maintain it

properly.

Disk Maintenance

To create partitions, you use fdisk or mkfs. To verify disk integrity, use the

fsck command.

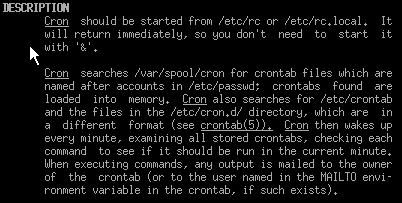

Scheduling jobs

You use the cron command to schedule tasks. Make sure you know how it works

before passing the test. The man cron output will tell you all you need to know

about it.

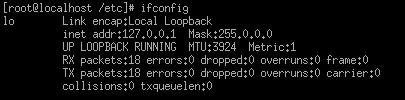

Network Maintenance

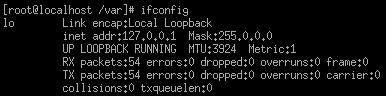

To view network statistics and configuration, use the ifconfig command.

System Maintenance and Updates

Most Linux distributions like RedHat have automatic update systems now. However,

you should know how to use the rpm or tgz command to install downloaded packages

in case of a problem. The patches are generally available from your

distribution’s website.

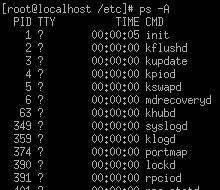

Process Maintenance

To view which processes are running, use the ps command. Generally you

will type ps –A (capital A - remember that linux is case sensitive!)

To kill a process, enter the kill command followed by the process ID (or

PID). Use killall to kill all processes.

Backup and Restore

Backing up a Linux machine is vital. A lot of third party software exists and

can make this process easier. Building a backup script is possible but not

always recommended since it can represent a lot of work. Check out

http://www.linux-backup.net for

more information on the subject.

Maintenance Good Practices

As with any other operating system, you should always develop good habits while

doing maintenance. More specifically, you should look at the following:

-

Document the work

performed on your Linux system

-

Regularly monitor the

log files. Verify errors and any unusual behavior.

-

Verify backups and do

restore tests.

-

Perform and check

security best practices: change passwords, disable unused resources and

accounts, verify file permissions, isolate important files and lock them

down with minimal permissions, do security audits if possible.

7.

Troubleshooting

In

order to make troubleshooting as easy as possible, you should always use an

organized methodology. Using simple best practices will do just that.

Best practices

The best tip when it comes to troubleshooting best practices is to document all

of your operations. This will prove helpful in critical situation as you will be

able to find out about service dependencies, permission issues, etc. Start with

quick fixes: if a problem sounds familiar, try using a couple of quick tricks.

This often addresses the issue. Do not act randomly: use a proper order to find

a problem. E.g. beginning by looking at hardware, then software, looking at

recent changes, looking at logs, asking the user about the nature of the problem

(sometimes the problem can be the user), etc. If all symptoms seem to point at a

certain service or process, you can kill and restart it.

You are expected to be able to inspect and determine cause of errors from system

log files using such commands as locate, find, grep, ? , <, >, >>, cat, tail.

A lot of error messages in linux come from different versions of software and

the dependencies associated with them. If you change or update a php package for

example, a php based program might stop working. You should use the rpm

command to view proper dependencies, document any changes and verify

dependencies before making any changes.

Troubleshooting the file system

To verify and repair a file system, you can use the mount command to

enumerate the different partitions on the system and the fsck command to

repair them.

You can use the DF command to see the space used on each disk. Problems can

occur when a disk is full.

Troubleshooting the boot process

Even with the strongest file systems, failure will happen. You may encounter

situations where the system boots in single user mode. This is an operating mode

that doesn’t start all daemons and is useful for troubleshooting. In this mode

you will be given the opportunity to use different troubleshooting tools

including file system integrity using fsck. In the case where a system

won't boot, it is a good idea to boot from a floppy and inspect the filesystem

and boot sector. A boot disk should always contain fsck as it will enable you to

repair and rescue a damaged file system.

Troubleshooting backup and restore errors

Backups can fail for many reasons. The most common causes are media and drive

related issues. Most media requires proper maintenance and cleaning. Tape

corruption, low device space or write failures are common problems. Proprietary

software will have specific error messages and you should refer to your software

provider to verify them. Backups should always be handled with care. You should

do a regular restore test as it is not uncommon to see successful backups that

cannot be successfully restored.

Troubleshooting Networking

Linux, being based on one of the oldest network operating systems (UNIX), is

loaded with standard troubleshooting tools. Some of these tools are:

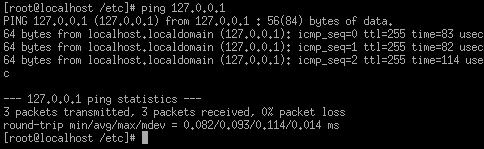

-

Ping: the ping utility

enables you to verify basic connectivity between two machines.

-

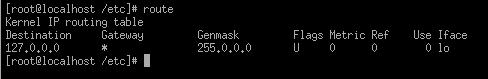

Route: the route

utility helps you take a look at the various routes defined within the

Kernels routing table. You will be able to add, delete, and modify routing

information here. This is very helpful when using your Linux box as a router

or firewall.

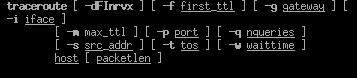

-

Traceroute: this

utility enables you to see every router between your Linux machine and a

given host. This way it is possible to see any failing point between you and

this host.

-

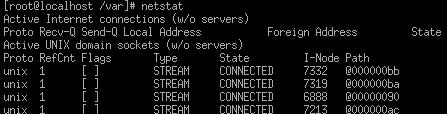

Netstat: this utility

helps you see your network interfaces statistics.

-

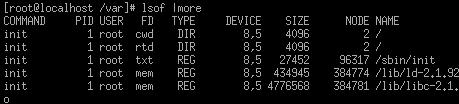

Lsof: this utility

lets you see any open files.

-

Ifconfig: this utility

lets you see your network interfaces and modify certain settings.

Finding

Help

Linux has one of the largest communities when it comes to finding friendly

support. Linux has specific terms when it comes to help. Here are a couple:

-

LUG: (Linux User

Group) LUGs are friendly groups of users and exist in most large cities

around the world. Lugs are a great way to have person to person support. You

can find most Lugs at the following URL

http://lugww.counter.li.org

-

Howto: A howto is a

detailed procedure for a specific topic regarding Linux. You can find a

howto to help you implement just about any Linux software or Linux service.

A great site about those can be found at

http://www.tldp.org.

-

Infopages: Those are

really popular in northern Europe and they are filled with useful

information. The hard part is finding one in English!

-

ManPages: Although

manpages are available in the shell, you are likely to find updated versions

of them all around the Web.

-

NHF: Newbie Help

Files. NHF’s are an initiative of justlinux.com (previously linuxnewbie.org).

They are easy to understand tutorials that will help new users understand

the nuts and bolts about specific linux topics. You will find NHF’s at

http://www.justlinux.com/nhf/.

-

Forums: remember that

you can always post your questions on a forum like the one found on

MC MCSE.

|